The temporal bones are bilateral and symmetrical, situated on each side of the skull. They form the base and sides of the skull, protecting the temporal lobes of the brain and surrounding the ear canals.

Temporal bone is not just a singular, solid bone but rather a complex assembly of different parts, each with specific functions. This bone encases the delicate structures of the ear, contributing to hearing and balance, and also forms part of the skull base, offering protection to the brain.

It’s a subject of interest in various medical fields due to its intricate connections and relevance to several sensory functions. For medical students, a thorough understanding of the temporal bone is essential for grasping the complexities of human anatomy and its clinical implications.

Anatomy of the Temporal Bone

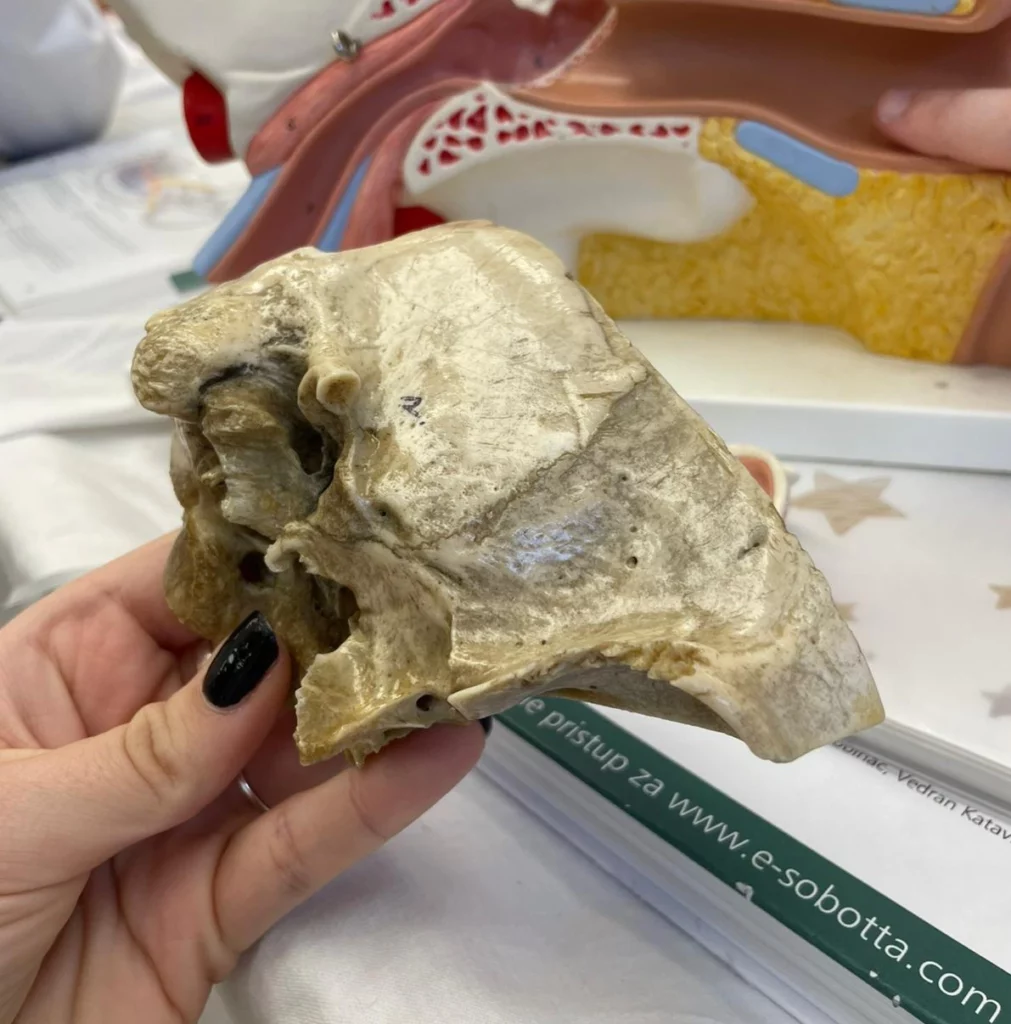

The temporal bone is composed of four distinct parts: squamous part, mastoid part, petrous part and tympanic part – each with unique features and roles.

Squamous Part

The squamous part is the largest and most superior section, forming the flat, palpable part of the temple. It’s thin and translucent, contributing to the side walls of the skull and providing attachment points for muscles. We can break down the squamous part of the temporal bone to the following structures:

Inner surface

The inner surface of the squamous part is smooth, hosting several grooves for arteries, contributing to cerebral blood supply. It also forms part of the middle cranial fossa, cradling the temporal lobe of the brain.

Outer surface

The outer surface is convex, contributing to the side of the head’s shape. It’s the site of muscle attachments, including the temporalis muscle, vital for jaw movement.

Processes and fossae

The zygomatic process, a prominent structure, extends from the squamous part to form part of the zygomatic arch. The mandibular fossa, a depression on this part, articulates with the mandible, facilitating jaw movement.

Borders

The squamous part borders with several cranial bones, including the parietal bone along the squamosal suture, illustrating the interconnectivity of skull bones.

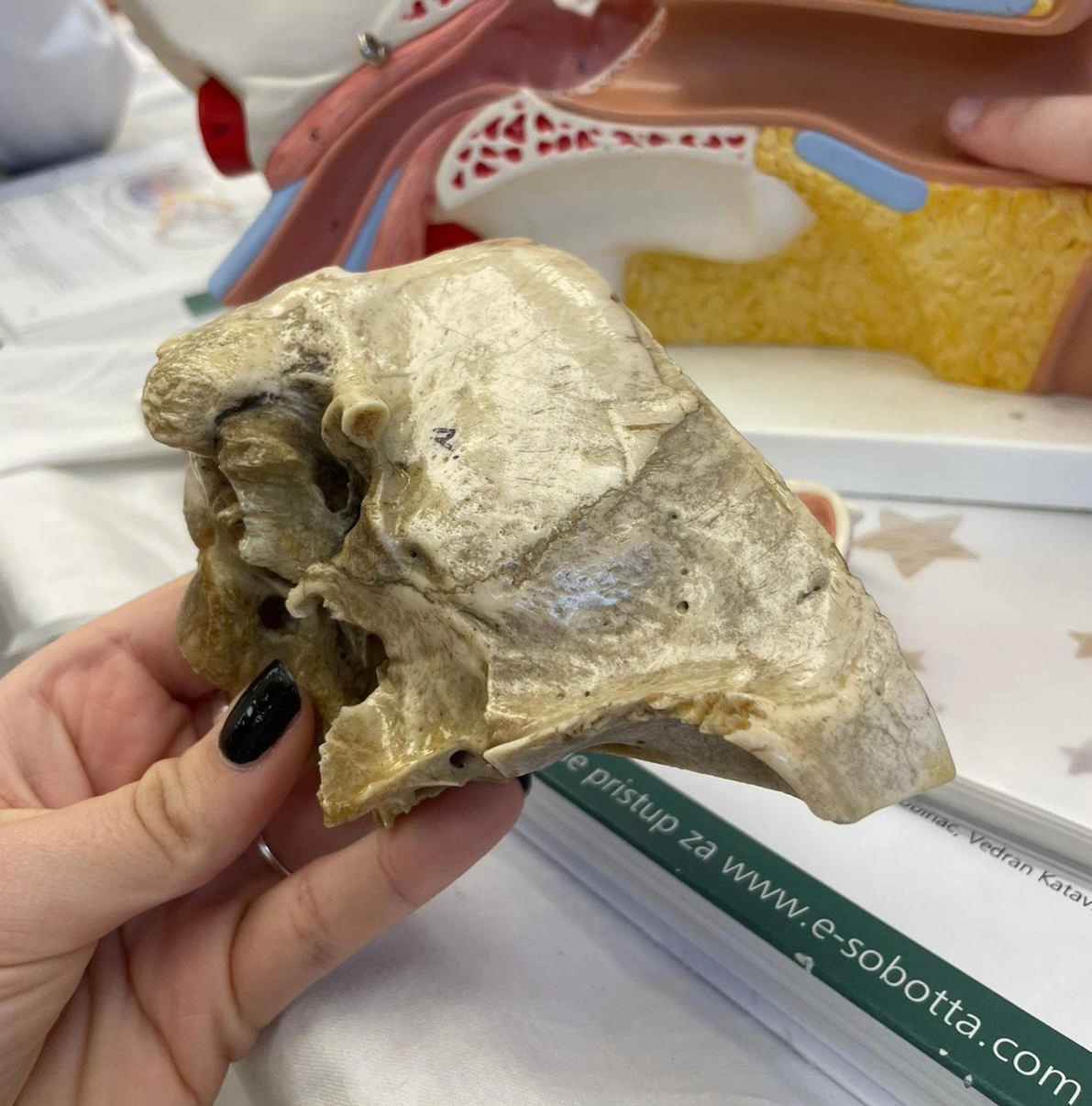

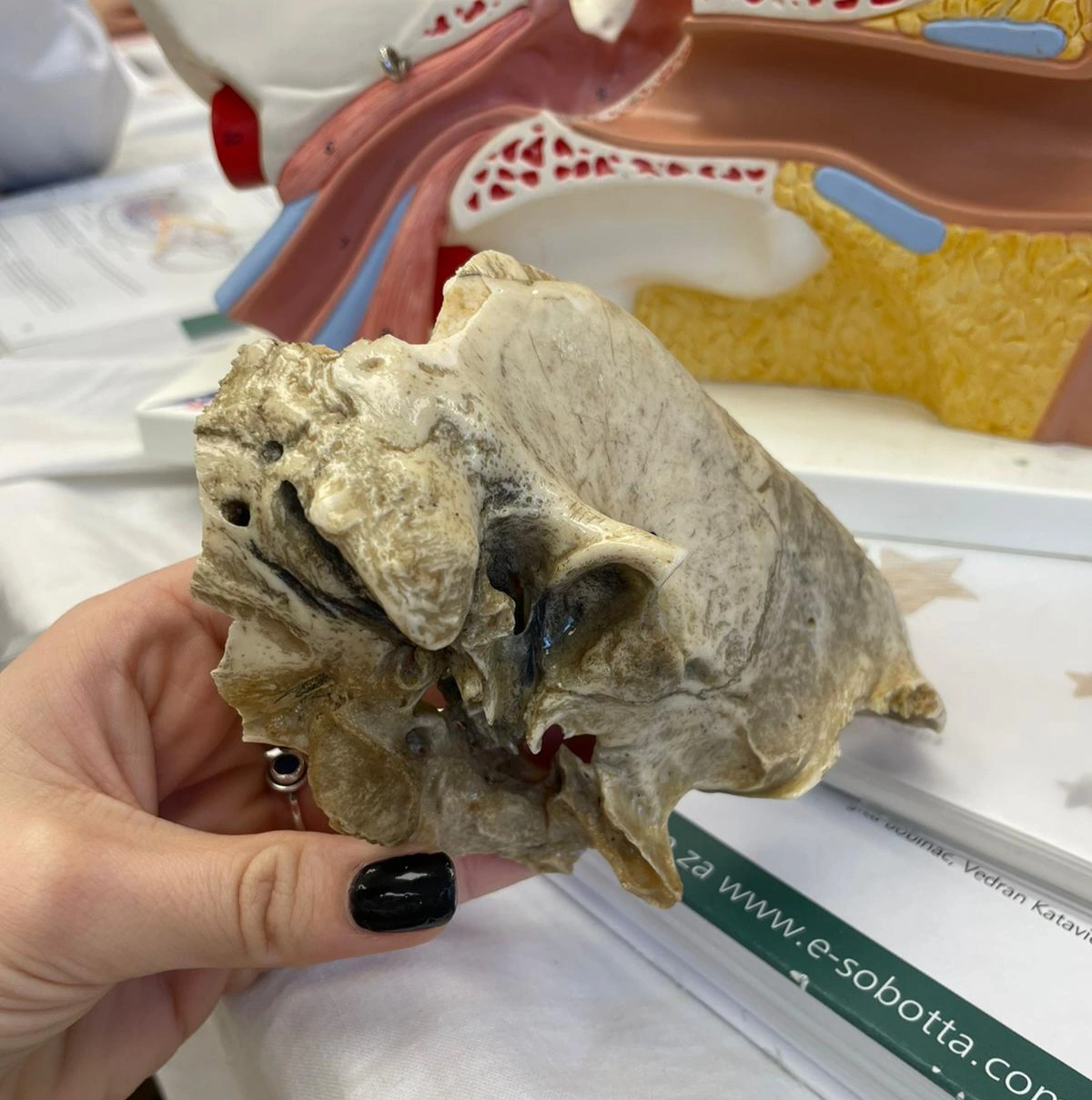

Mastoid Part of the Temporal Bone

Posterior and inferior to the ear canal, the mastoid part contains air cells that help regulate ear pressure. It’s easily identifiable as the bony prominence behind the ear.

Inner surface

The inner surface of the mastoid part is known for its proximity to the middle and posterior cranial fossae. It contains the mastoid antrum, a key air space that connects to the middle ear, playing a role in ear health.

Outer surface

The outer surface is identifiable as the mastoid process, a palpable landmark behind the ear. This process is important for muscle attachments, including those for the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which aids in head movement.

Processes and fossae

The mastoid part includes the mastoid notch, a groove that serves as the origin for the digastric muscle, important in swallowing and speech. The stylomastoid foramen, another feature, allows the facial nerve to exit the skull, influencing facial expressions.

Borders

It borders with the occipital bone, contributing to the occipitomastoid suture. This junction is significant in skull growth and development.

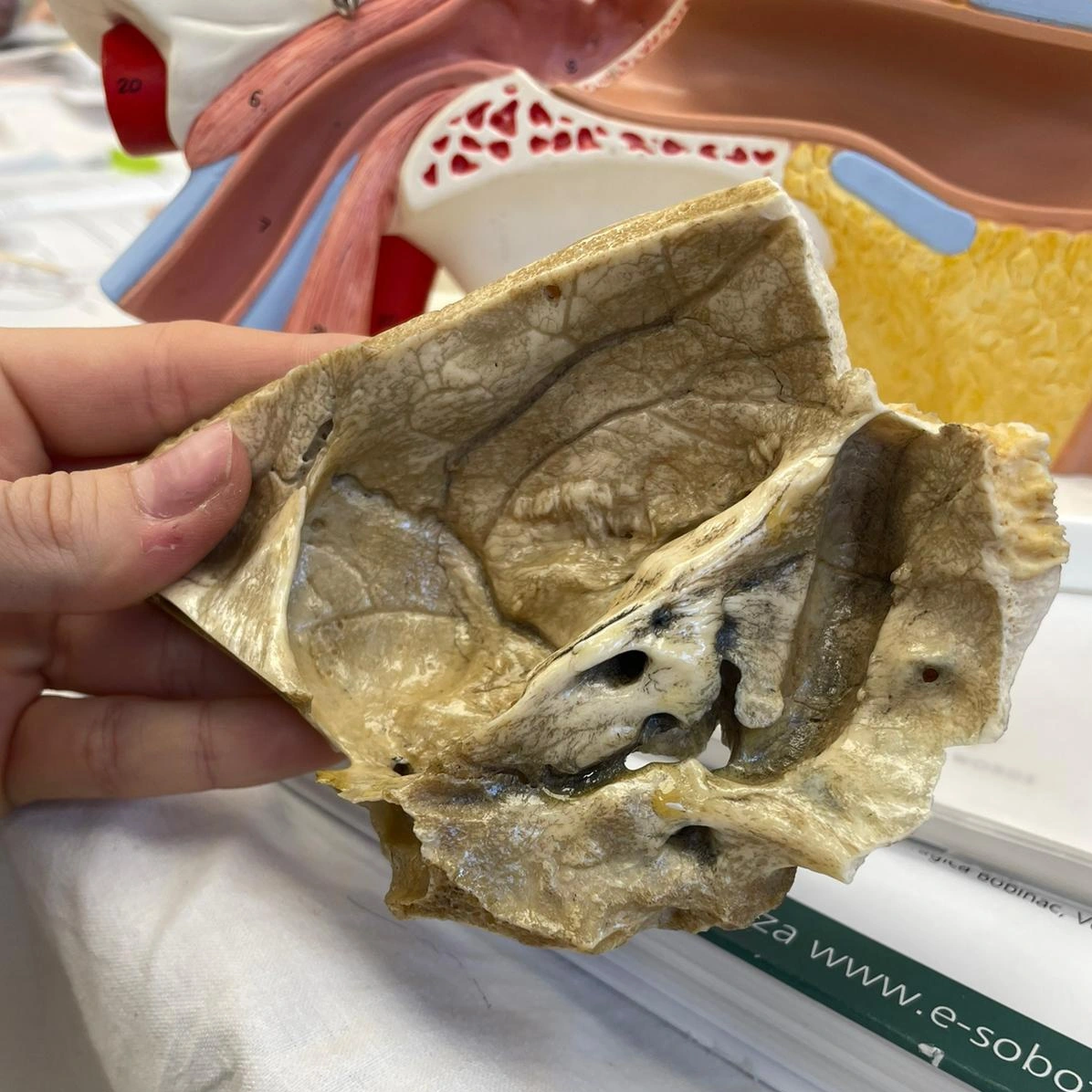

Petrous Part of the Temporal Bone

Dense and pyramid-shaped, the petrous part houses the inner ear structures. It’s the hardest bone in the human body, lying at the skull’s base, and plays a significant role in hearing and balance.

Base of the petrous part

The base of the petrous part forms part of the cranial floor, contributing to the skull’s structural integrity. It’s thick and houses sensitive structures like the cochlea and vestibular apparatus, essential for hearing and balance.

Apex of the petrous part

The apex of the petrous part points anteromedially towards the sphenoid bone. It is significant for its articulation with the basilar part of the occipital bone, playing a role in cranial stability.

Anterior surface od the petrous part

The anterior surface faces the middle cranial fossa and includes important foramina like the carotid canal, allowing passage of the internal carotid artery, vital for brain blood supply.

Posterior surface od the petrous part

This surface faces the posterior cranial fossa, containing the internal acoustic meatus, important for the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves, impacting hearing and balance.

Inferior surface od the petrous part

The inferior surface, part of the skull base, includes the jugular foramen, essential for venous drainage from the brain via the jugular vein.

Functions of the Temporal Bone

The temporal bone provides protection and support for the brain. It also houses the organs essential for hearing and balance. This bone serves as an attachment point for muscles involved in chewing and facial expressions, demonstrating its multifaceted role in cranial function.

Hearing and Balance

The temporal bone has an integral role in the auditory system. The external auditory canal, part of the tympanic section, channels sound waves towards the eardrum. Inside, the intricate ossicles of the middle ear (housed within the petrous part) transmit vibrations to the cochlea. The cochlea, a spiral-shaped organ, converts these vibrations into nerve impulses, which are interpreted as sound by the brain.

The petrous part also contains the vestibular apparatus, responsible for maintaining balance. This system detects head movements and positional changes, sending signals to the brain to help maintain equilibrium and spatial orientation.

Protection of Inner Ear Structures

The temporal bone’s robust structure provides protection for the inner ear. The petrous part, being the hardest bone in the body, encases delicate structures like the cochlea and vestibular organs, safeguarding them from external impacts and infections.

Its density and position at the base of the skull also shield these sensory organs from potential damage due to trauma. Furthermore, the air cells within the mastoid part of the temporal bone play a role in protecting the middle ear from pressure changes, ensuring the delicate mechanisms involved in hearing and balance remain functional and intact.

Attachment Point for Muscles Involved in Chewing and Facial Expressions

The temporal bone’s significance extends to its role as an anchor for various muscles. The mastoid process, a notable feature of the mastoid part, serves as an attachment point for muscles like the sternocleidomastoid, which plays a role in head movement and posture.

The squamous part provides attachment for the temporalis muscle, important for chewing movements. Additionally, the styloid process, extending from the temporal bone, is involved in anchoring muscles and ligaments that support the tongue and pharynx, influencing speech and swallowing. These attachment points are essential for many daily activities like eating, speaking, and expressing emotions, highlighting the temporal bone’s role in functional anatomy.

Development and Ossification

The development and ossification of the temporal bone are complex processes that begin early in embryonic life and continue into early adulthood.

Embryology of the Temporal Bone

The embryological development of the temporal bone begins in the early weeks of gestation. It originates from multiple embryonic structures, including the first and second pharyngeal arches. These arches contribute to forming the ear’s components and associated structures.

As the fetus develops, these embryonic segments differentiate and grow, laying the foundation for the future temporal bone. This developmental process is vital for the correct formation of the ear. It ensures the ear’s associated functions in hearing and balance, which we have already covered.

Ossification Process

Ossification of the temporal bone is a multi-stage process that begins in utero and continues into adolescence. It involves the gradual transformation of cartilage or fibrous structures into bone. This process varies across the different parts of the temporal bone, with some areas ossifying earlier than others.

The petrous part, for instance, begins ossifying early and plays a role in protecting the developing inner ear. The timing and sequence of these ossification events are essential for the proper anatomical and functional development of the ear and related structures.

Blood Supply and Innervation of the Temporal Bone

The blood supply to the temporal bone is provided through a network of arteries, primarily from the branches of the external carotid artery, ensuring efficient nourishment and oxygenation of the area. Innervation of the temporal bone is equally complex, involving cranial nerves that facilitate sensory and motor functions, including hearing, balance, and facial movements.

Arteries and Veins Associated with the Temporal Bone

Major arteries, like the branches of the external and internal carotid arteries, supply blood to the various parts of the temporal bone. Veins accompany these arteries, ensuring efficient blood drainage. The vascular supply is important for nourishing the bone and supporting the auditory and vestibular systems housed within it.

Nervous System Connections

The innervation of the temporal bone is linked to several cranial nerves. Key among these are the facial nerve (VII) and the vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII).

The facial nerve traverses the temporal bone, controlling muscles of facial expression. The vestibulocochlear nerve is central to hearing and balance. Additionally, smaller nerves contribute to sensation and function in and around the ear. This complex neural network is significant for the integrated functioning of the auditory and vestibular systems.

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance of the temporal bone cannot be overstated, especially in the fields of otolaryngology and neurology. Its complex anatomy and functions make it a central focus in many medical conditions and treatments.

Common Diseases and Disorders

The temporal bone is susceptible to various diseases and disorders, significantly impacting hearing and balance.

Conditions like otitis media, an infection of the middle ear, and mastoiditis, an infection of the mastoid air cells, are common. These conditions not only affect hearing but can also lead to more serious complications if left untreated. We need to understand these disorders for effective diagnosis and management.

Temporal Bone in Surgical Procedures

In surgery, the temporal bone presents both challenges and opportunities. Procedures involving this bone require precision due to the proximity of critical structures like the facial nerve and inner ear.

Surgeries can range from mastoidectomy to remove infected bone tissue, to more complex interventions for tumors or to correct congenital abnormalities. The role of the temporal bone in surgical contexts underscores the importance of detailed anatomical knowledge for safe and effective treatment.

Imaging and Diagnostic Techniques

Imaging and diagnostic techniques offer comprehensive insights into the complex structure of the temporal bone and associated pathologies. Advanced methods such as CT and MRI scans provide high-resolution images that enable precise assessment of the bone and surrounding soft tissues. This level of detail is essential for diagnosing a range of conditions, from infections and fractures to tumors and congenital anomalies, leading to more accurate treatment strategies and better patient outcomes.

X-rays, CT, and MR

X-rays, though basic, can provide initial insights into the bone structure. However, CT (Computed Tomography) scans are more effective for detailed bone imaging, especially in complex areas like the temporal bone.

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is invaluable for soft tissue evaluation, including nerves and inner ear structures. These imaging modalities complement each other, providing comprehensive views of the temporal bone’s anatomy and potential abnormalities.

Importance in Diagnostics and Treatment Planning

Imaging is an invaluable technique in diagnosing conditions affecting the temporal bone. It helps in identifying the extent of diseases, such as infections or tumors, and is essential for planning surgical procedures.

Accurate imaging ensures precise targeting during surgery, minimizing risks to critical structures like nerves and blood vessels. In conditions affecting hearing and balance, these techniques are indispensable for determining the cause and extent of impairment, guiding effective treatment strategies.

Conclusion

The temporal bone, with its complex anatomy comprising the squamous, mastoid, petrous, and tympanic parts, plays important roles in hearing, balance, and protection of inner ear structures.

Its development, from embryology to ossification, is intricate. The bone’s blood supply, innervation, and susceptibility to various diseases highlight its clinical importance. Imaging techniques like X-rays, CT, and MRI are invaluable for its assessment, influencing diagnosis and treatment planning.

The Temporal Bone’s Role in Overall Health and Medicine

The temporal bone’s functions extend beyond the auditory system, influencing overall health and well-being. Its protection of inner ear structures, support in facial expressions and chewing, and involvement in numerous medical conditions underscore its significance in medicine. A comprehensive understanding of the temporal bone is therefore essential for medical professionals, as it impacts a wide array of clinical practices and patient care.

Study with MedBrane

If you’re keen to deepen your understanding of human anatomy, give the MedBrane app a try. It’s free and offers a great way to gauge what you already know through thorough exam simulations. Plus, you can learn as you go with in-depth explanations for every question.

Also you can follow us on Instagram @medbrane for more anatomy and study tips!