Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a life-threatening medical condition characterized by the sudden blockage of one or more arteries in the lungs, usually by blood clots originating from deep veins in the legs or pelvis.

Pulmonary embolism accounts for up to 10% of intra-hospital mortality. It is the third most common cardiovascular disease after heart attack and stroke. The risk of developing a pulmonary embolism can increase during long periods of inactivity, such as during long flights or car rides, leading to the condition sometimes being referred to as “economy class syndrome”.

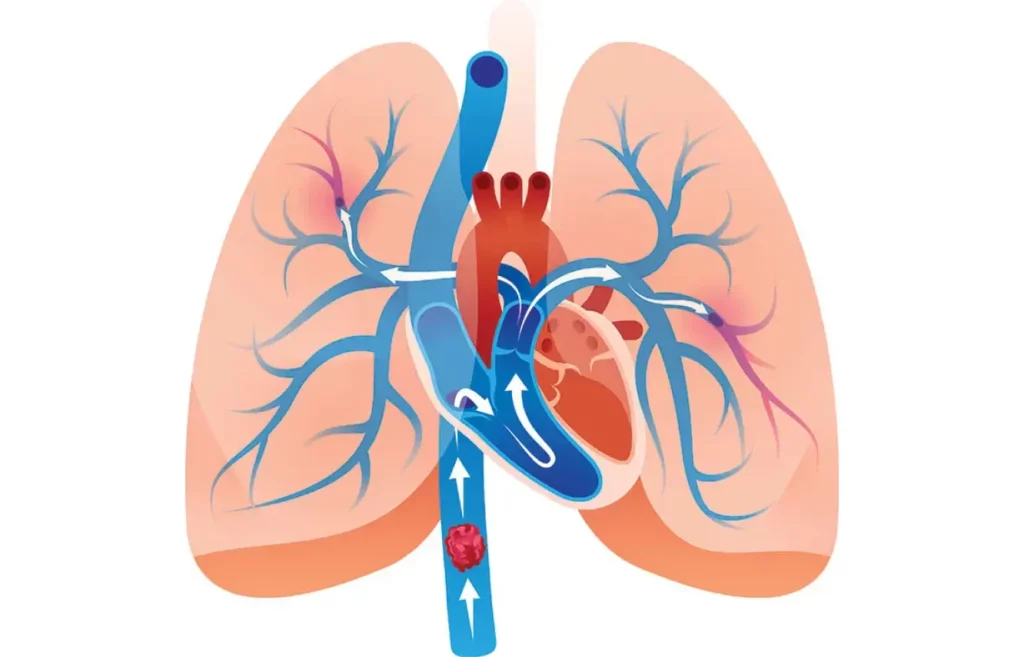

Pathophysiology of Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary embolism typically occurs when a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) dislodges and travels through the venous system, reaches the right side of the heart and eventually lodges in the pulmonary arteries. This results in obstruction of blood flow to the lungs, causing a range of symptoms (depending on the size of the thrombus and the location of the embolization), from mild dyspnea to hemodynamic instability, shock, and death.

Risk factors for PE include recent surgery, immobility, malignancy, a history of DVT, pregnancy, and exposure to certain medicines. Virchow’s triad, comprising hypercoagulability, endothelial injury, and stasis, plays a central role in PE development.

Diagnosis

Clinical presentation is essential for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. It often includes signs and symptoms such as an abrupt onset of dyspnea, tachycardia, pleuritic chest pain, and cough.

The two main diagnostic tools for examining dyspnea and chest pain are ECG and X-ray. In PE, they are usually normal. Therefore, the absence of evidence of myocardial infarction, cardiac tamponade, aortic dissection, and pneumonia should guide the physician to consider pulmonary embolism as a differential diagnosis. An abrupt onset of dyspnea and a normal chest X-ray are highly indicative of PE!

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

The most common ECG finding is sinus tachycardia, present in up to 90% of patients. The McGinn-White sign or ‘S1Q3T3’ is present in only 10% of cases and usually suggests a hemodynamically significant PE.

There might also be T wave inversion in the precordial leads (V1-V4), which is known as the ‘right ventricular strain pattern’, and right bundle branch block might also be present.

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

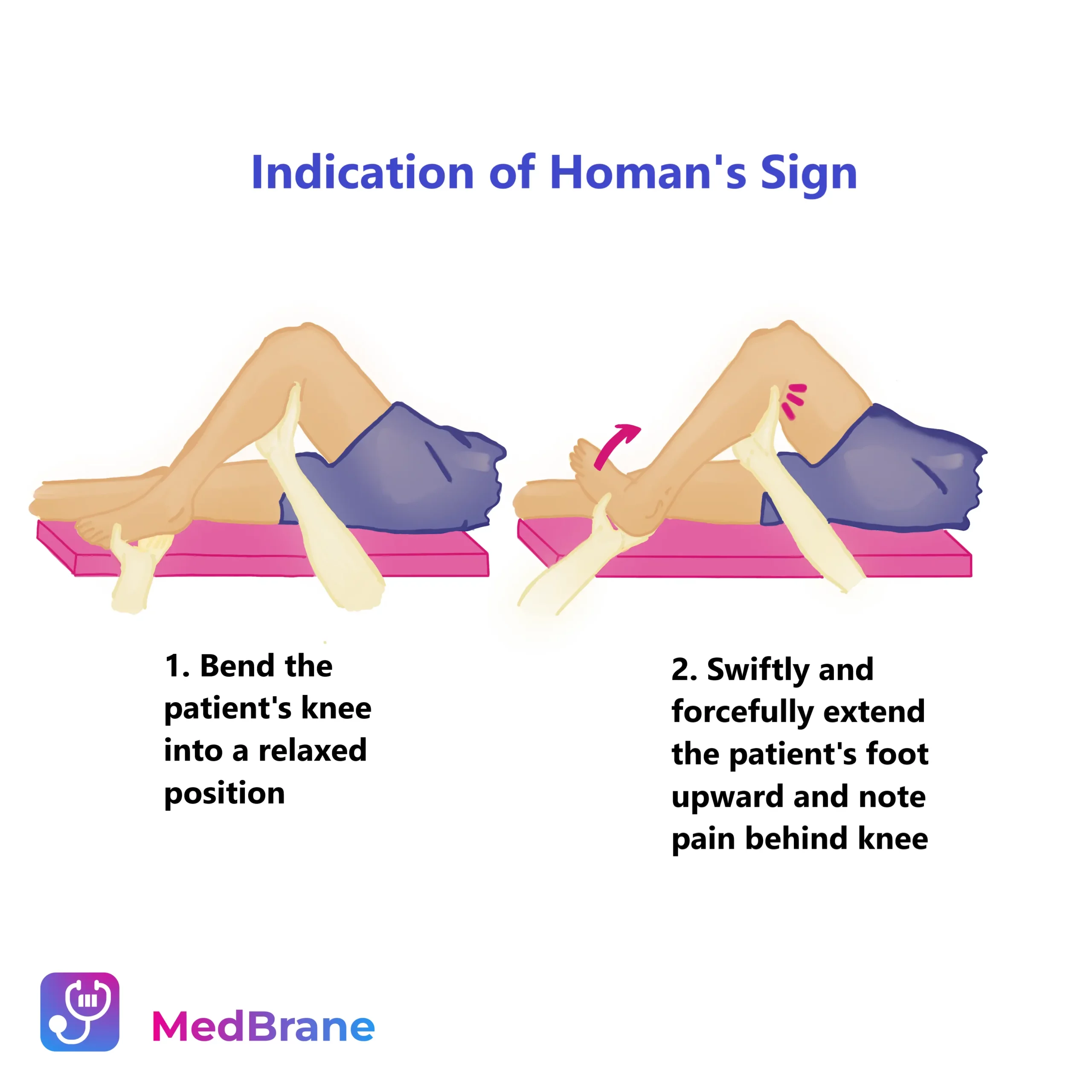

Since the most common cause of pulmonary embolism is a deep vein thrombosis (usually of the leg or pelvic veins), patients should be examined for signs of deep vein thrombosis. Unilateral leg edema is highly suspicious of DVT. Leg pain, cramping, soreness, and discomfort often starting in the calf are common symptoms. The Homan’s sign, which involves pain in the calf upon dorsiflexion of the foot, is helpful in the diagnosis. Ultrasound of the femoral and popliteal veins is also a useful tool in DVT diagnosis.

D-dimers have a high negative predictive value. What does that mean? If the D-dimers are low and the patient has no immediate risk factors, PE should be ruled out. Other causes of dyspnea should be evaluated.

ECHO can be useful in evaluating right ventricular dysfunction in PE. There are some specific findings that help in the diagnosis of PE, such as the McConnel sign and the 60/60 sign.

CT angiography is the gold standard in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism and it confirms the diagnosis.

Acid-base status can be insightful in PE. The most common finding is low PaO2, low or normal PaCO2 (due to hyperventilation) and metabolic acidosis (due to peripheral tissue hypoxia).

Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scanning can be an alternative diagnostic tool in the absence of the CT scan.

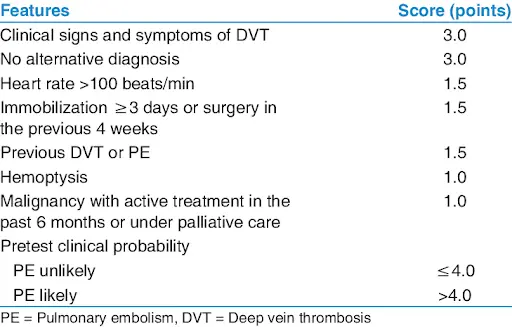

The Wells Criteria for PE helps assess pretest probability:

Treatment

Pulmonary embolism management depends on the patient’s risk profile:

Low-Risk pulmonary embolism

Anticoagulation therapy with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) followed by oral anticoagulants (warfarin or direct oral anticoagulants) is the standard treatment. Consideration of thrombolysis is generally not indicated for low-risk patients.

High-Risk pulmonary embolism

Patients with hemodynamic instability or severe right ventricular dysfunction may benefit from thrombolytic therapy (e.g., alteplase). In cases of impending or massive PE, emergent surgical or catheter-based interventions like embolectomy or catheter-directed thrombolysis can be considered.

Who is “hemodynamically unstable”? Patients with hypotension (blood pressure less than 90/60), kidney failure, distended jugular veins, high central venous pressure, and patients who presented with sudden cardiac arrest.

Clinical Pearls and Take Home Messages

- Abrupt onset of dyspnea and normal chest x-ray are highly suspicious of PE!

- ECG findings in PE may include sinus tachycardia (in 90% of cases), S1Q3T3 pattern and right ventricular strain pattern (inverted T waves in V1-V4).

- Low PaO2, low or normal PaCO2, and metabolic acidosis are suggestive of PE.

- Remember that the Wells Criteria rule can help guide the diagnostic approach.

- In patients with contraindications to anticoagulation, inferior vena cava filters should be considered.

- Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is a long-term complication of PE, emphasizing the importance of follow-up.

- Patients with unexplained PE (PE without established risk factors) should be screened for abdominal cancer.

- Anticoagulation therapy should be continued for at least 6 weeks and up to 6 months. Male sex and high D-dimers a month after the anticoagulation was discontinued are predictors of the relapse of the PE.

- DVT can cause thromboembolic stroke if it bypasses the pulmonary circulation through the atrial septal defect. This is known as the paradoxical embolism.

- PE is included in the 4Ts of reversible causes of cardiac arrest (thrombosis, tamponade, toxicity, and tension pneumothorax).

Conclusion

To wrap things up, mastering the subject of pulmonary embolism is really important for medical students studying for the USMLE Step 2 CK. It’s key to grasp how it develops, how to diagnose it, and how to treat it to ensure top-notch patient care.

Make sure to memorize the main signs and symptoms, the scoring methods, and how to handle PE cases that vary in severity. Lastly, hold onto these handy insights – they’ll help you shine both in your clinical work and on your exams.

Study with MedBrane

If you’re keen to deepen your understanding of pulmonary embolism and other pathology subjects, give the MedBrane app a try. It’s free and offers a great way to gauge what you already know through thorough exam simulations. Plus, you can learn as you go with in-depth explanations for every question.