Case presentation

A 67 year-old man with COPD is somnolent with shallow breathing.

ABG: pH 7.25,

PaCO₂ 60 mmHg,

HCO₃⁻ 26 mEq/L.

Arrow method

For each ABG variable, imagine an arrow showing its direction from normal.

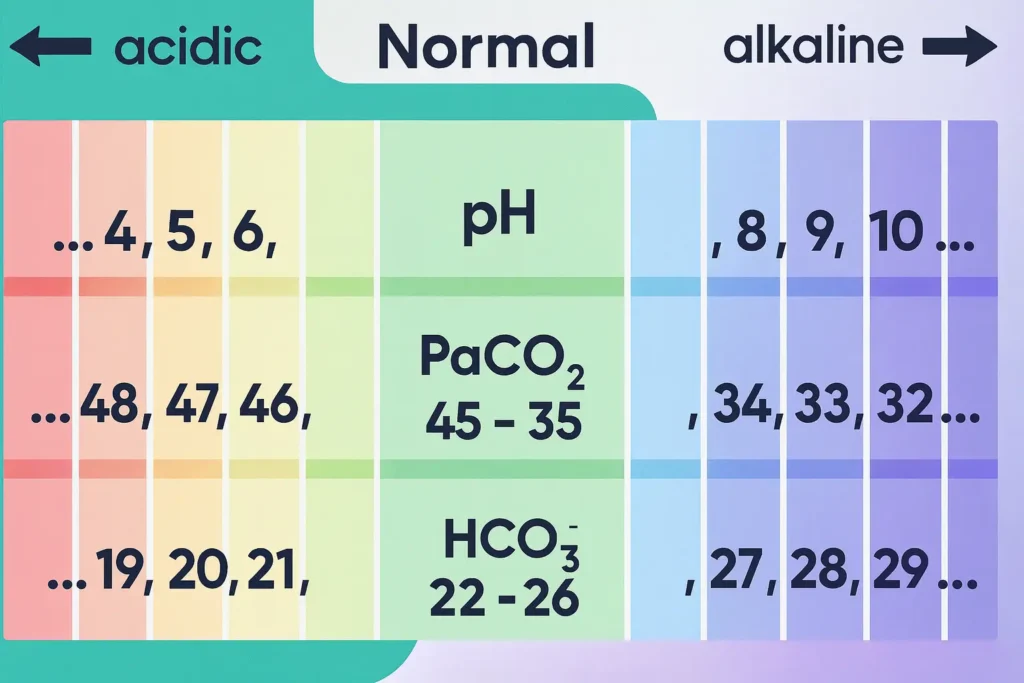

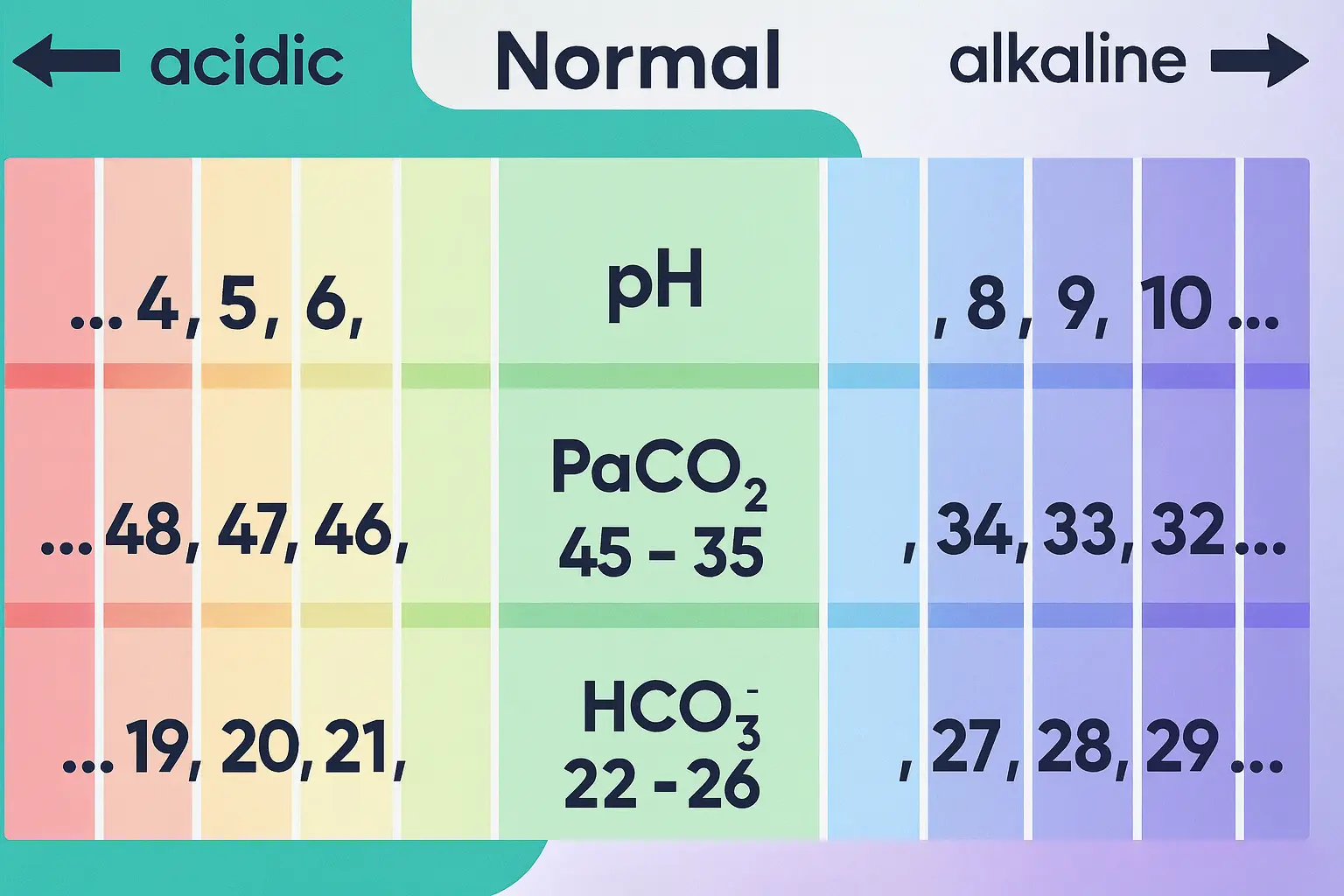

- pH 7.35-7.45: < 7.35 → ↓, > 7.45 → ↑.

- PaCO₂ 35-45 mmHg: > 45 → ↑, < 35 → ↓.

- HCO₃⁻ 22-26 mEq/L: > 26 → ↑, < 22 → ↓.

Use the arrows in three moves:

- pH first (acidemia = ↓, alkalemia = ↑).

- Compare PaCO₂ to pH. If arrows are ‘REVERSE’ (opposite), the primary process is respiratory. If arrows are ‘SAME’ (or PaCO₂ is still normal), the primary process is metabolic.

- Check HCO₃⁻ to confirm the primary process and to grade compensation (uncompensated vs partially/fully compensated).

Apply to the case: pH ↓; PaCO₂ ↑ → ‘REVERSE’ → respiratory acidosis. HCO₃⁻ is near normal → acute/uncompensated.

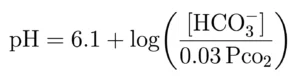

The physiology follows Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

Pathophysiology

Buffer system and controllers

- CO₂ is the volatile acid. PaCO₂ depends on alveolar ventilation. Hypoventilation increases PaCO₂ (respiratory acidosis). Hyperventilation decreases PaCO₂ (respiratory alkalosis). Respiratory responses occur within minutes.

- HCO₃⁻ is controlled by the kidneys through proximal bicarbonate reabsorption and distal H⁺ secretion with titratable acid and NH₄⁺ generation. Renal responses require hours to days.

- Net pH reflects the ratio HCO₃⁻/PaCO₂, not their absolute values.

Expected compensations (detect mixed disorders)

Use these to test whether the measured compensation is appropriate.

Metabolic acidosis → respiratory compensation (Winter’s formula):

Predicted PaCO₂ = 1.5 × [HCO₃⁻] + 8 ± 2.

Measured PaCO₂ > predicted → concomitant respiratory acidosis.

Measured PaCO₂ < predicted → concomitant respiratory alkalosis.

Metabolic alkalosis → expected hypoventilation:

Predicted PaCO₂ ≈ 0.7 × [HCO₃⁻] + 20 ± 5.

(Approximate rule: PaCO₂ rises 0.5–1.0 mmHg per 1 mEq/L increase in HCO₃⁻.)

Respiratory acidosis (PaCO₂ ↑):

- Acute: HCO₃⁻ ↑ ~1 mEq/L per 10 mmHg PaCO₂ rise.

- Chronic (≥ 3-5 days): HCO₃⁻ ↑ ~ 3.5-4 mEq/L per 10 mmHg.

Respiratory alkalosis (PaCO₂ ↓):

- Acute: HCO₃⁻ ↓ ~ 2 mEq/L per 10 mmHg fall.

- Chronic: HCO₃⁻ ↓ ~ 4-5 mEq/L per 10 mmHg.

These limits define the maximum physiologic compensation; values beyond them imply a second primary disorder.

Anion gap and delta checks (for metabolic acidosis)

AG = Na⁺ – (Cl⁻ + HCO₃⁻).

Normal ≈ 8-12 mEq/L (without K⁺).

- High AG metabolic acidosis causes → GOLDMARK:

Glycols (ethylene, propylene), Oxoproline (chronic acetaminophen), L-actate, D-lactate, Methanol, Aspirin (late), Renal failure (uremia), Ketones (diabetic, alcoholic, starvation). - Normal AG (hyperchloremic) metabolic acidosis: diarrhea, pancreatic/enteric fistulas, renal tubular acidosis(types 1, 2, 4), saline load, acetazolamide, ureteral diversions, hypoaldosteronism.

Delta-delta to unmask mixed metabolic processes in high-AG acidosis:

- ΔAG = AG – 12; ΔHCO₃⁻ = 24 – HCO₃⁻.

- If ΔAG > ΔHCO₃⁻ → concurrent metabolic alkalosis.

- If ΔAG < ΔHCO₃⁻ → added non-gap metabolic acidosis.

Or use the delta ratio = ΔAG/ΔHCO₃⁻: 1.0-2.0 typical; > 2 suggests metabolic alkalosis; < 1 suggests additional non-gap acidosis.

Diagnostics

Stepwise interpretation with arrows

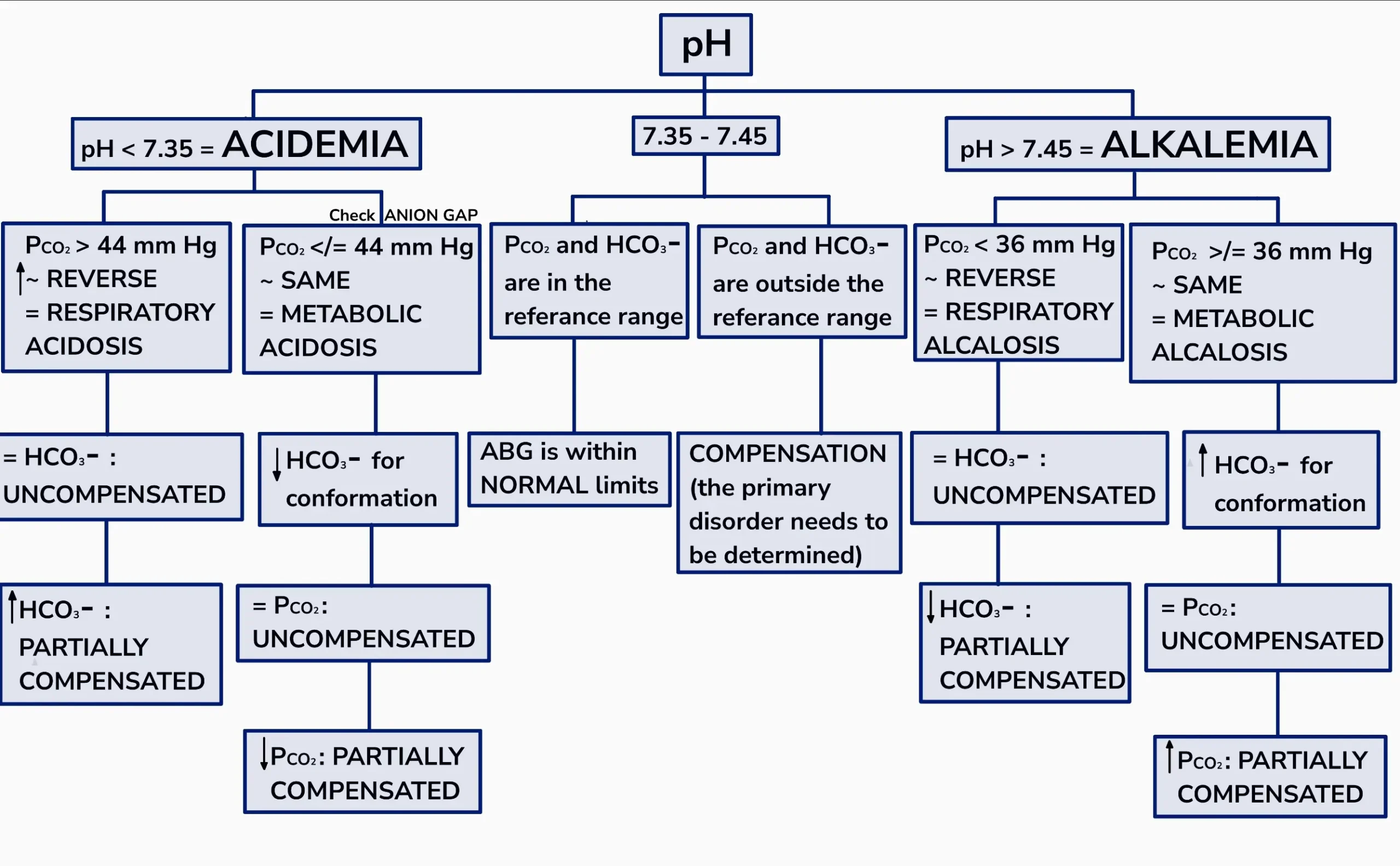

Step 1 – pH.

- 7.35-7.45:

- If PaCO₂ 35-45 and HCO₃⁻ 22-26 → normal ABG.

- If PaCO₂ or HCO₃⁻ are outside of range while pH is normal → compensation or a balanced mixed disorder; test with compensation formulas.

- pH < 7.35 (↓): acidemia.

- pH > 7.45 (↑): alkalemia.

Step 2 – PaCO₂ (compare to pH arrow).

- Acidemia + PaCO₂ ↑ (REVERSE) → respiratory acidosis.

- Acidemia + PaCO₂ ↓ or normal (SAME) → metabolic acidosis.

- Alkalemia + PaCO₂ ↓ (REVERSE) → respiratory alkalosis.

- Alkalemia + PaCO₂ ↑ or normal (SAME) → metabolic alkalosis.

Step 3 – HCO₃⁻ (confirm and stage compensation).

- In respiratory disorders, HCO₃⁻ magnitude separates acute from chronic as above.

- In metabolic disorders, HCO₃⁻ direction confirms the diagnosis (↓ in acidosis, ↑ in alkalosis) and PaCO₂ should move appropriately by the expected formula.

Step 4

If metabolic acidosis, compute the AG (and corrected AG), then perform delta-delta.

Step 5

If metabolic alkalosis, measure a spot urine chloride.

- Urine Cl⁻ < 10-20 mEq/L → chloride-responsive (vomiting/NG suction, remote diuretics, post-hypercapnia).

- Urine Cl⁻ ≥ 20 mEq/L → chloride-resistant (mineralocorticoid excess, current diuretics, Bartter, Gitelman).

Typical causes to consider while applying the steps

Respiratory acidosis (PaCO₂ ↑, pH ↓):

Airway obstruction (asthma, COPD), severe pneumonia/ARDS with fatigue, central hypoventilation (opioids, sedatives, brainstem lesions), neuromuscular failure (myasthenia, Guillain–Barré), chest wall restriction, obesity hypoventilation.

Respiratory alkalosis (PaCO₂ ↓, pH ↑):

Anxiety/pain, hypoxemia from pneumonia/PE/high altitude, early sepsis, pregnancy, liver disease, hyperthyroidism, CNS disorders, early salicylate toxicity.

Metabolic acidosis (HCO₃⁻ ↓, pH ↓):

- High AG: GOLDMARK list above.

- Normal AG: diarrhea, RTA types 1/2/4, saline load, acetazolamide, ureterosigmoidostomy.

Metabolic alkalosis (HCO₃⁻ ↑, pH ↑):

- Chloride-responsive: vomiting/NG suction, prior loop/thiazide use, post-hypercapnic state.

- Chloride-resistant: primary hyperaldosteronism, Cushing syndrome, ongoing diuretics, Bartter/Gitelman, severe hypokalemia and/or hypomagnesemia.

Ancillary calculations and labs

- Serum osmolality for suspected toxic alcohols: 2×Na⁺ + glucose/18 + BUN/2.8 + ethanol/4.6. Osmolar gap > 10-20 mOsm/kg supports a toxic alcohol ingestion when paired with high-AG acidosis.

- Lactate, ketones, salicylate level, ethanol, renal function, urinalysis (for RTA clues), pregnancy test when appropriate.

- Ventilation status (respiratory rate, tidal volume, minute ventilation) when PaCO₂ is abnormal.

Treatment

General principles

- Treat the underlying cause.

- Compensation is limited; do NOT target a “normal” pH by forcing compensation beyond physiologic limits.

- Correct volume, electrolytes (K⁺, Cl⁻, Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺), and oxygenation.

- Address extreme pH values promptly (pH ≤ 7.1 or ≥ 7.6).

Respiratory acidosis

- Airway and ventilation: positional maneuvers, bronchodilators and systemic steroids for obstructive disease, antibiotics when infection is present, chest physiotherapy when indicated.

- Reverse depressants (e.g., naloxone for opioids, flumazenil use is restricted; consider only in selected benzodiazepine cases).

- Non-invasive ventilation for COPD exacerbations or obesity hypoventilation if no contraindications; intubationif deteriorating.

- Oxygen to correct hypoxemia; in chronic hypercapnic COPD target SpO₂ 88-92% unless there are other indications.

- Bicarbonate infusion is not standard for isolated respiratory acidosis. Consider only if there is concurrent severe metabolic acidosis with life-threatening acidemia while ventilation is being corrected.

Respiratory alkalosis

- Treat the trigger: analgesia, temperature control, anxiolysis and breathing coaching, treat hypoxemia, manage sepsis, treat PE or pneumonia.

- Ventilated patients: reduce minute ventilation (lower tidal volume and/or respiratory rate) while maintaining oxygenation.

- No role for acid administration.

Metabolic acidosis

- High AG causes

- Diabetic ketoacidosis: isotonic fluids, insulin, potassium repletion, treat precipitating factor. Give bicarbonate only when pH ≤ 6.9-7.0 or with severe hyperkalemia or refractory shock.

- Lactic acidosis: restore perfusion and oxygen delivery, early antibiotics for sepsis, source control; stop causative drugs (e.g., metformin in renal failure). Consider renal replacement therapy (RRT) for severe persistent acidosis or concurrent indications.

- Toxic alcohols (ethylene glycol, methanol): fomepizole (or ethanol when appropriate), adjunctive hemodialysis for high levels, severe acidosis, or end-organ injury.

- Salicylate poisoning: alkalinize serum and urine with IV sodium bicarbonate and potassium, avoid intubation if possible (risk of abrupt CO₂ rise and acidosis), and dialyze when indicated.

- Renal failure: initiate dialysis for refractory acidosis, hyperkalemia, volume overload, or uremic complications.

- Normal AG causes

- Diarrhea/enteric losses: isotonic saline with KCl replacement; treat the cause.

- Renal tubular acidosis: give alkali (sodium bicarbonate or potassium citrate) to normalize HCO₃⁻ and prevent nephrolithiasis/bone disease; correct hyperkalemia in type 4 RTA (fludrocortisone for mineralocorticoid deficiency when indicated, or loop/ thiazide diuretics and sodium bicarbonate).

- General bicarbonate strategy

- Consider IV bicarbonate when pH ≤ ~ 7.1 with hemodynamic instability, arrhythmia risk, or when rapid reversal of the primary cause is not possible.

- Monitor sodium load, volume status, ionized calcium (may fall), and CO₂ generation.

Metabolic alkalosis

- Chloride-responsive (urine Cl⁻ < 10-20 mEq/L)

- Isotonic saline and potassium chloride are first-line.

- Stop gastric H⁺ loss (PPI, remove NG suction when possible).

- Reduce or discontinue diuretics if feasible; if diuretics must continue, replace Cl⁻ and K⁺ aggressively.

- Chloride-resistant (urine Cl⁻ ≥ 20 mEq/L)

- Treat mineralocorticoid excess (spironolactone/eplerenone), manage adrenal causes, consider surgery for aldosterone-producing adenoma.

- For ongoing diuretic effect or sodium retention states, consider amiloride.

- Correct Mg²⁺ and K⁺ deficits.

- Volume-overloaded patients (e.g., heart failure) with metabolic alkalosis: acetazolamide promotes bicarbonate diuresis and can be used with loop diuretics.

- Refractory, life-threatening alkalemia: consider HCl infusion via central line or dialysis in experienced settings.

Prognosis

- Prognosis is driven by the cause, severity of pH derangement, and speed of correction.

- pH < 7.1 increases risk of myocardial depression, vasodilation, ventricular arrhythmias, and reduced response to catecholamines.

- pH > 7.55-7.60 increases risk of arrhythmias, decreased cerebral blood flow, seizures, and hypokalemia-related complications.

- In reversible causes with rapid treatment (e.g., DKA, panic hyperventilation, salicylate exposure treated early), outcomes are good.

- In chronic diseases (advanced COPD, kidney failure), recurrent disturbances are common; outcome follows the primary illness.

- Mixed disorders in the ICU correlate with disease severity but respond when each component is identified and treated.

Epidemiology

- Acid-base disorders are common in hospitalized patients and very common in critical care.

- Metabolic acidosis is frequent in sepsis/shock, renal failure, and DKA.

- Respiratory alkalosis occurs in hypoxemia, pregnancy, liver disease, early sepsis, and anxiety/pain.

- Respiratory acidosis is typical of hypoventilation due to COPD exacerbation, sedative drug effect, neuromuscular failure, or obesity hypoventilation.

- Metabolic alkalosis is prevalent with vomiting/NG suction and diuretic therapy; endocrine causes are less common but clinically important.

ABG examples (practice with arrows)

Example 1

ABG: pH 7.28, PaCO₂ 30 mmHg, HCO₃⁻ 14 mEq/L.

Arrows: pH ↓, PaCO₂ ↓ (SAME) → metabolic acidosis.

Winter’s predicted PaCO₂ = 1.5×14 + 8 = 29 ±2 → measured 30 = appropriate compensation.

Compute AG. If AG 24, ΔAG 12, ΔHCO₃⁻ 10; ΔAG > ΔHCO₃⁻ → added metabolic alkalosis.

Example 2

ABG: pH 7.52, PaCO₂ 28, HCO₃⁻ 23.

Arrows: pH ↑, PaCO₂ ↓ (REVERSE) → respiratory alkalosis.

HCO₃⁻ normal → acute.

Example 3

ABG: pH 7.44, PaCO₂ 55, HCO₃⁻ 36.

pH normal. Because PaCO₂ and HCO₃⁻ are both high, this is compensated chronic respiratory acidosis (e.g., COPD). Check chronic compensation: for a 10-mmHg rise above 40 (i.e., +15), expected HCO₃⁻ rise ≈ ~ 5-6 mEq/L; measured 36 (baseline 24 + ~ 5-6 = 29-30) suggests additional metabolic alkalosis; clinical correlation needed (e.g., diuretics).

Example 4

ABG: pH 7.48, PaCO₂ 50, HCO₃⁻ 36.

Arrows: pH ↑, PaCO₂ ↑ (SAME) → metabolic alkalosis.

Predicted PaCO₂ ≈ 0.7×36 + 20 = 45 ±5 → measured 50 is compatible with compensation.

Urine Cl⁻ guides treatment: < 20 → saline + KCl; ≥ 20 → evaluate for mineralocorticoid excess or current diuretics.

Algorithm (using arrows)

- Draw three arrows based on normal ranges (pH, PaCO₂, HCO₃⁻).

- pH first:

- ↓ = acidemia; ↑ = alkalemia; normal may be normal or compensated/mixed.

- Compare PaCO₂ to pH:

- REVERSE → respiratory primary.

- SAME (or PaCO₂ normal) → metabolic primary.

- Use HCO₃⁻ to confirm and to grade compensation (plus acute vs chronic for respiratory disorders).

- If metabolic acidosis → anion gap (correct for albumin) → delta–delta for mixed metabolic problems.

- If metabolic alkalosis → urine Cl⁻ to separate chloride-responsive vs chloride-resistant.

- Check expected compensation with the appropriate formula to unmask mixed disorders.

- Treat the cause, correct dangerous extremes, replace electrolytes, and support ventilation and perfusion.