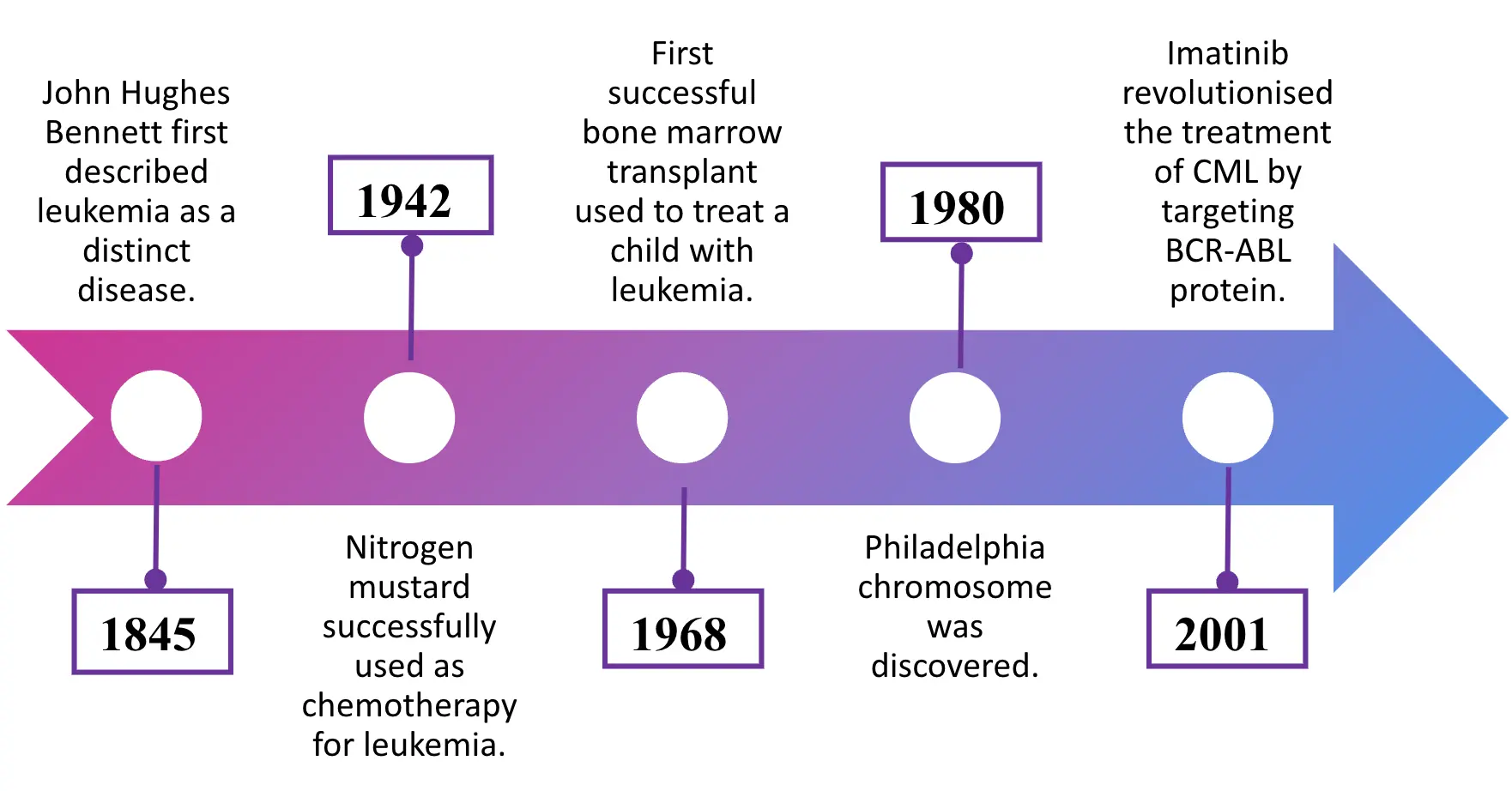

Leukemias are unnecessarily complicated for medical students, so today we are here to help and simplify! Dive into the world of leukemia with MedBrane’s guide tailored for medical students!

What is Leukemia?

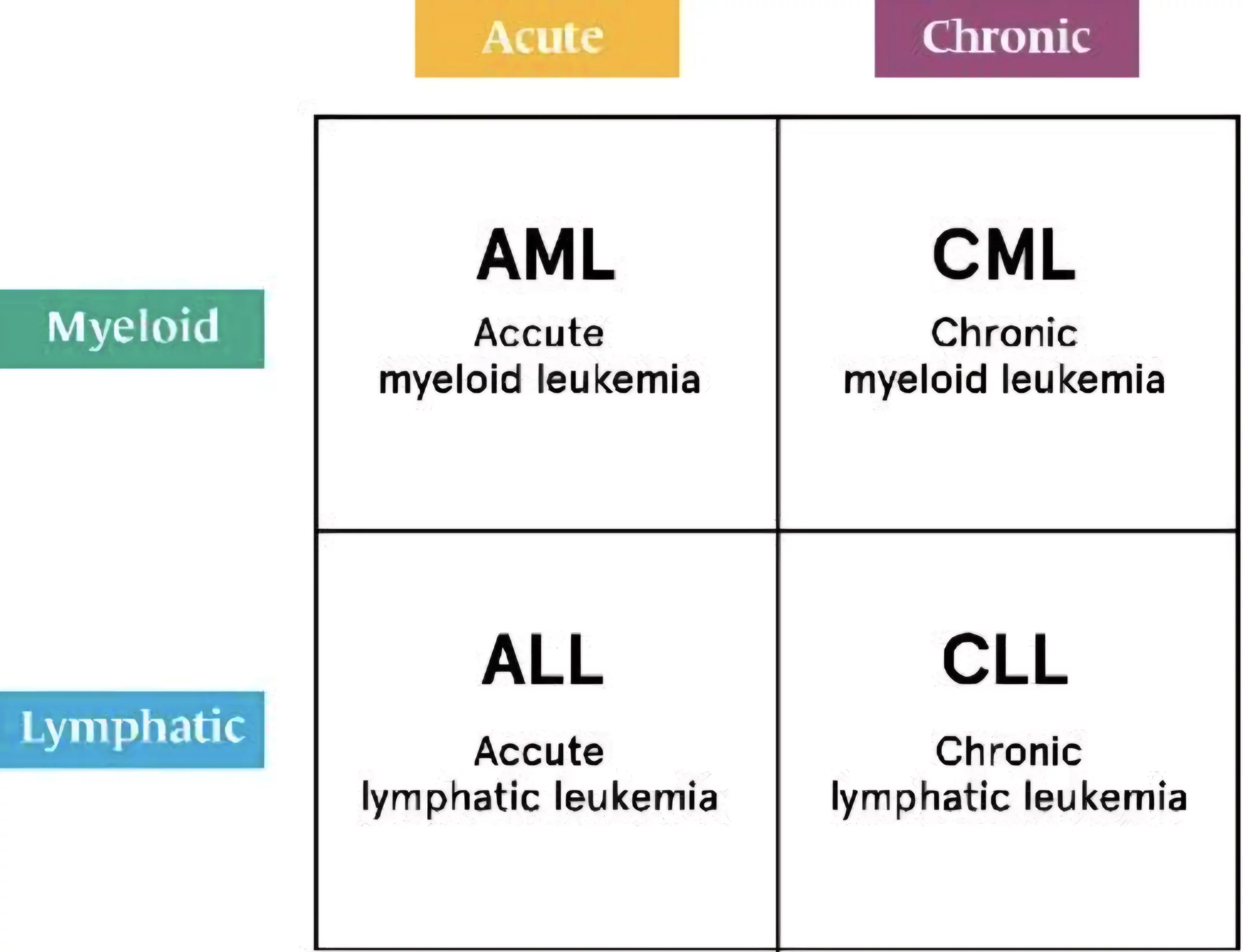

Leukemias are a group of hematological malignancies characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of leukocytes in bone marrow. It is classified into four main types based on the speed of progression (acute or chronic) and the type of blood cell affected (lymphoid or myeloid). This classification forms the foundation for understanding leukemias:

- Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

- Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML)

Why do Leukemias Happen?

Leukemias arise from genetic and environmental factors.

Genetically, certain inherited syndromes like Down syndrome (trisomy 21) and Li-Fraumeni syndrome (p53 mutation) increase leukemia risk. Moreover, specific chromosomal translocations such as BCR-ABL, also known as Philadelphia chromosome, play a key role in oncogenesis.

The BCR gene, located on chromosome 22, and the ABL gene, on chromosome 9, form the BCR-ABL fusion gene via the Philadelphia chromosome translocation. This fusion protein has constant tyrosine kinase activity, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation, driving chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and some acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases.

Environmental exposures, including ionizing radiation and benzene, also contribute to oncogenesis. Additionally, infections like the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) are linked to specific leukemias.

Pathophysiology of Leukemia

Let’s go over some of the basic pathophysiological mechanisms that apply to all leukemias.

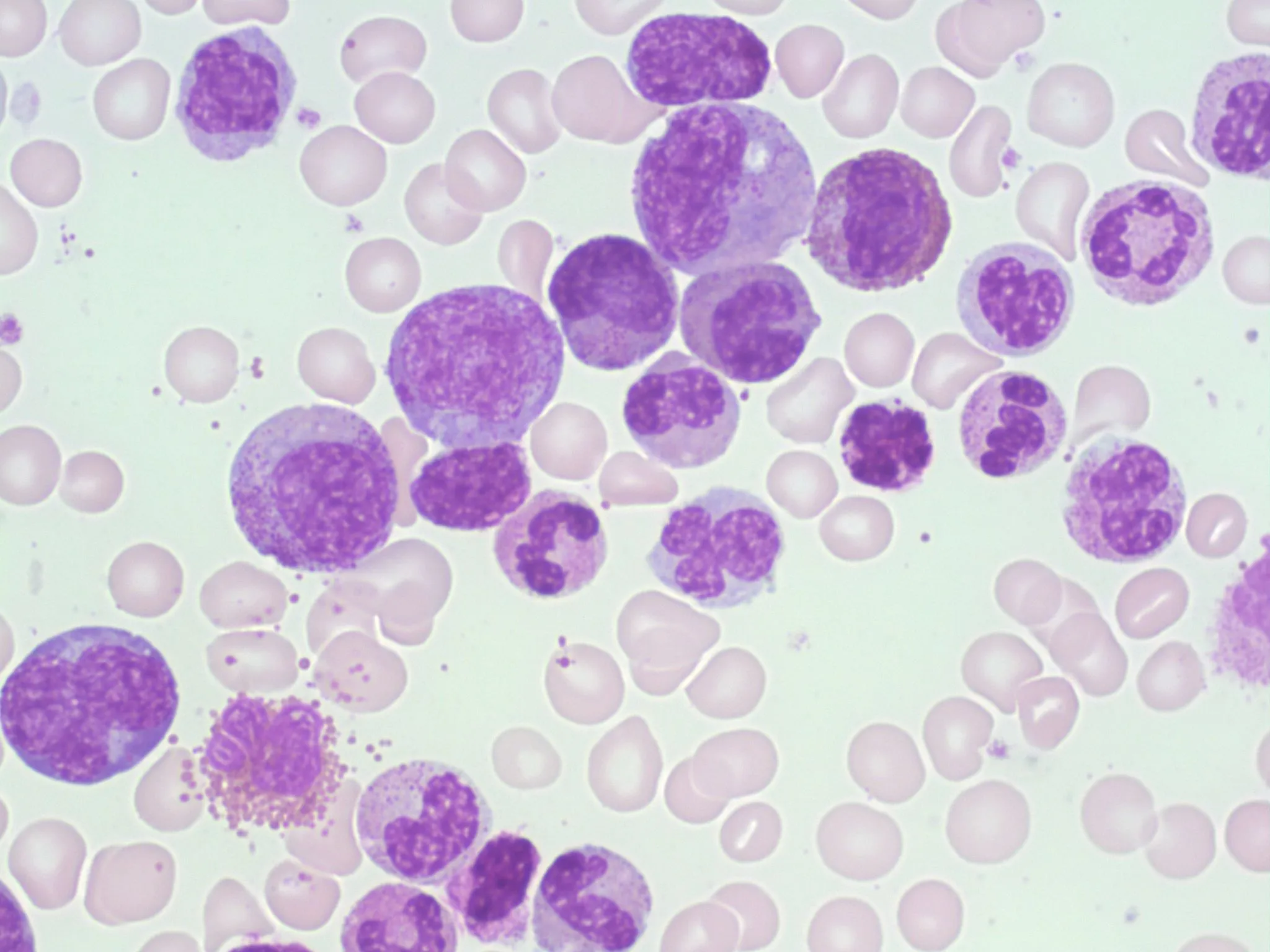

Leukemic pathophysiology involves the accumulation of immature leukocytes due to disrupted hematopoietic differentiation and apoptosis. Genetic mutations and epigenetic alterations activate signaling pathways such as JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT, enhancing leukemic cell proliferation and survival. Furthermore, leukemic cancer cells evade immune surveillance through downregulation of MHC molecules.

The overproduction of these dysfunctional leukemic cells suppresses normal hematopoietic cells, leading to anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. This severely compromises the immune system by reducing the number of functional leukocytes and impairing their ability to activate an effective immune response. Therefore, patients are immunocompromised, prone to infections, and prone to bleeding due to thrombocytopenia.

Acute vs Chronic leukemia

Acute leukemia is a rapidly progressing cancer of the blood and bone marrow characterized by the accumulation of immature blood cells. Chronic leukemia is a slowly progressing disease where mature but abnormal white blood cells accumulate.

Myeloid vs lymphocytic leukemia

Myeloid leukemias originate from myeloid stem cells, which develop into red blood cells, platelets, and some white blood cells. In contrast, lymphoblastic leukemias arise from lymphoid stem cells, affecting lymphocyte development.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL ) predominantly affects children and is less common in adults. A subtype involving T-cells may present as a mediastinal mass, mimicking superior vena cava syndrome. ALL is notably associated with Down syndrome and is characterized by the presence of lymphoblasts in both peripheral blood and bone marrow.

Key markers for diagnosis include TdT+ (found in pre-T and pre-B cells) and CD10+ (specific to pre-B cells). While ALL is generally responsive to therapy, it can spread to the CNS and testes. The t(12;21) translocation suggests a better prognosis, whereas the t(9;22) Philadelphia chromosome is linked to a poorer outcome.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

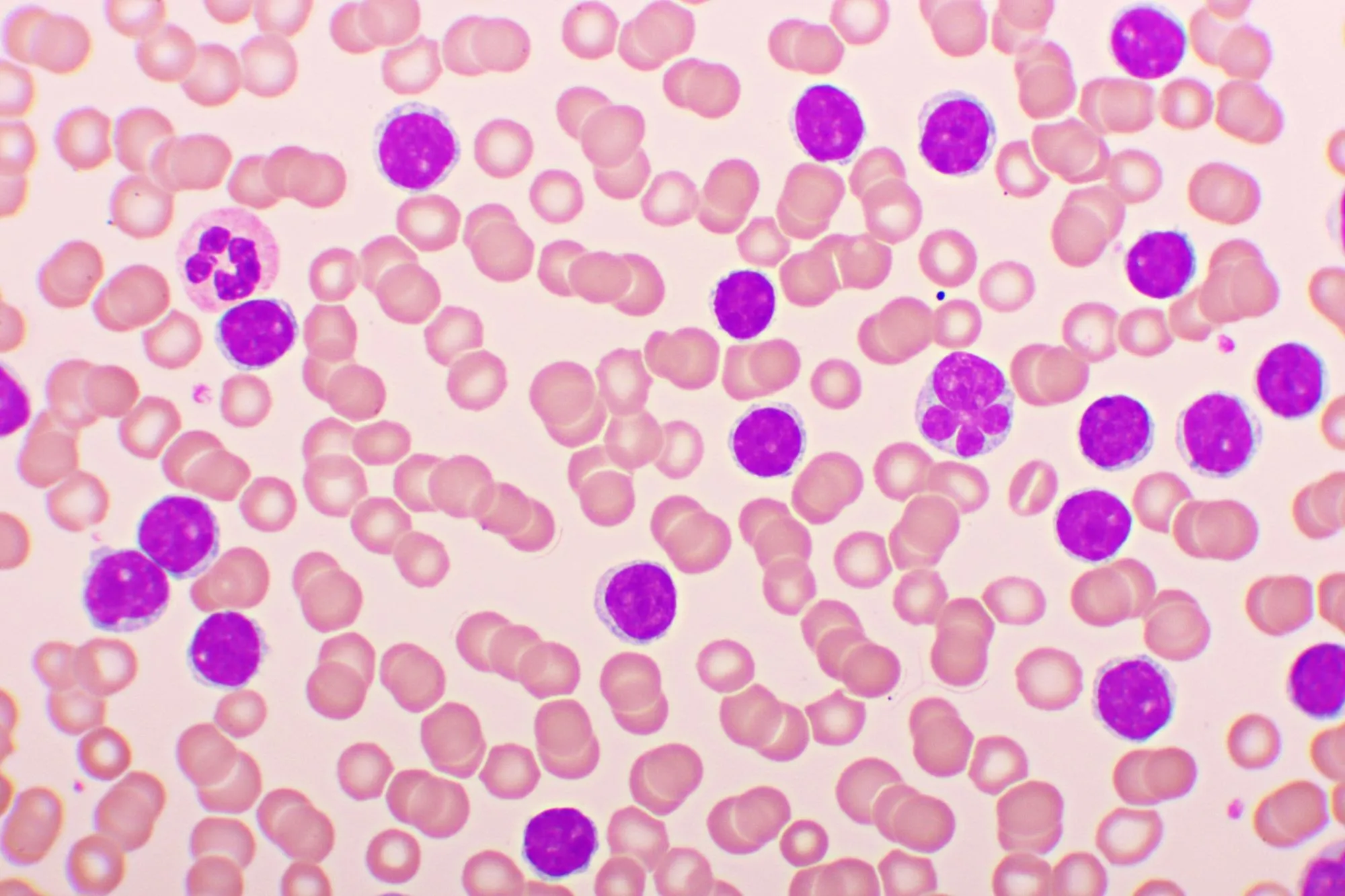

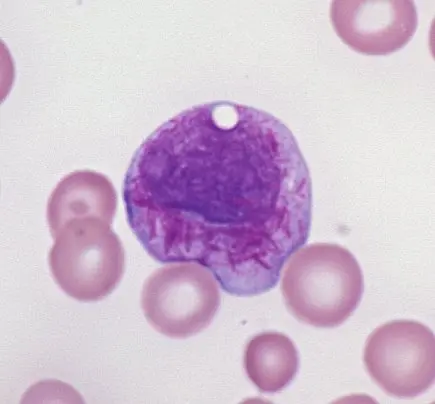

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, typically occurring in those over 60 years old. It is a slow-progressing B-cell neoplasm characterized by CD20+, CD23+, and CD5+ markers. CLL often presents asymptomatically and is identified by the presence of “smudge cells” (also known as Crushed Little Lymphocytes – CLL) on a peripheral blood smear. Patients may develop autoimmune hemolytic anemia. A notable complication is Richter transformation, where CLL transforms into a more aggressive lymphoma, most commonly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Hairy cell leukemia

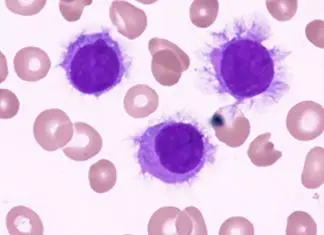

Hairy cell leukemia is a rare mature B-cell tumor that predominantly affects adult males. The leukemia cells are distinctive, with filamentous, hairlike projections visible under light microscopy. The disease often leads to bone marrow fibrosis, resulting in a “dry tap” during aspiration. Patients typically present with massive splenomegaly and pancytopenia.

Hairy Cell Leukemia stains positive for Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP). The disease is associated with BRAF mutations and is treated effectively with purine analogs such as cladribine and pentostatin.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia

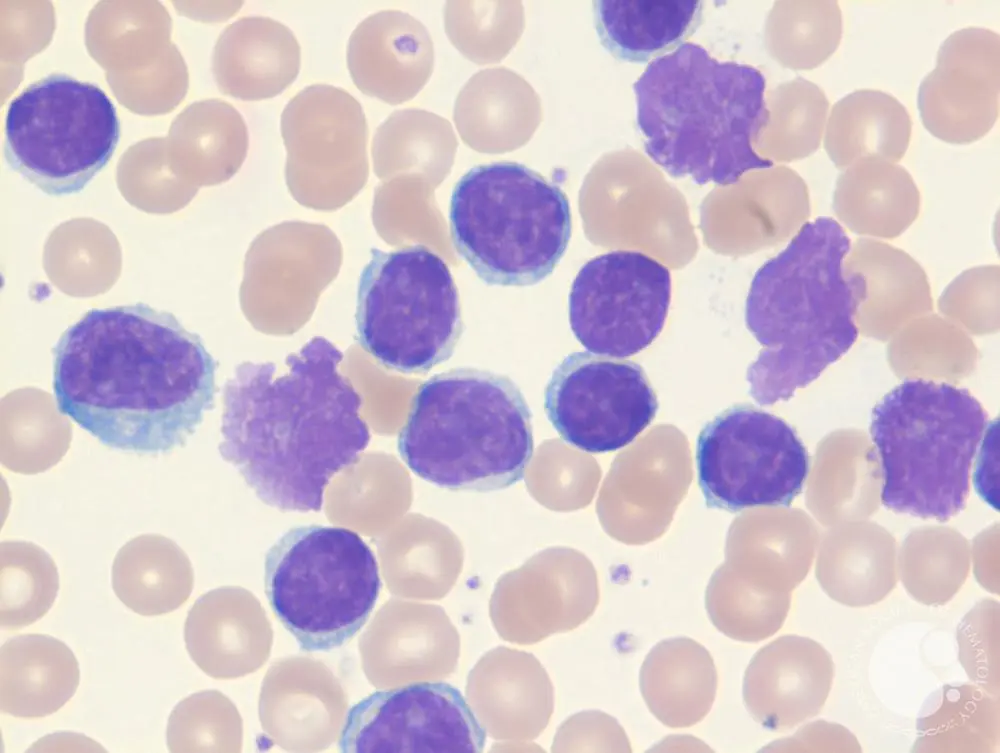

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) typically presents in individuals with a median age of 65. It is characterized by the presence of Auer rods and myeloperoxidase-positive cytoplasmic inclusions. Peripheral blood smears often reveal circulating myeloblasts. Patients may present with leukostasis, a condition where capillary occlusion by rigid, malignant cells leads to organ damage. Risk factors for AML include prior exposure to alkylating chemotherapy, radiation, benzene, myeloproliferative disorders, and Down syndrome.

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) occurs in adults with a peak incidence between 45 and 85 years. It is characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome (t[9;22], BCR-ABL), leading to myeloid stem cell proliferation. Patients often present with dysregulated production of mature and maturing granulocytes and splenomegaly. CML can progress to a more aggressive phase known as a “blast crisis” transforming into either AML or ALL. The disease responds well to treatment with BCR–ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib.